Archival surfaces

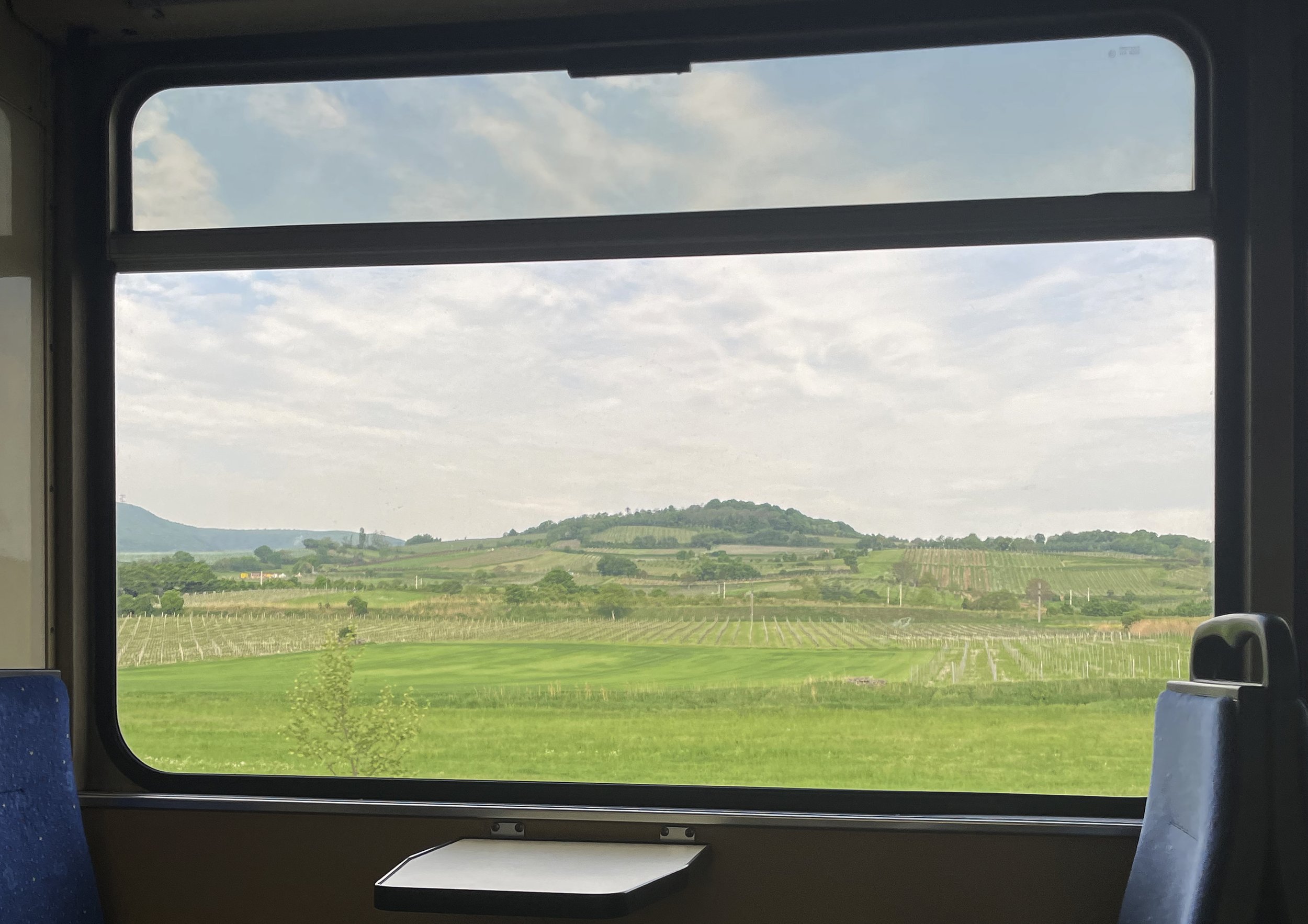

Daily route by Badner Bahn to get from Vienna to the Az W depot in Möllersdorf

What we always knew but never looked at

How can you touch the digital? Does it smell? Can architectural research trace the action and thinking process of both architects and archivists to uncover memories and thus knowledge about linked events? Assuming that material serves as a situation rather than an object – how might these situations be embodied? Or rather, can the archive actually embody knowledge?

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been delving into the world of archives, or rather archiving. The interesting thing to me about the practice of archiving is that the author of the collected material starts with his/her particular practice of collecting and the archivist will then continue – very often without ever having been in contact with the author. There is trust in these archival materials that I have tried to reflect on the process of encountering the physical material and transferring it to the digital world, the database of the Architekturzentrum Wien (AzW).

In a world that relies on the digital, trust in knowledge continues to be held in a material object, an electronic device. When the pandemic hit us, we were all surprised at how quickly we adapted to new forms of habits in our lives. We can do more than we thought we could. How can the bodies of people engaged with the archival material still be visible in the future? Perhaps by making the knowledge transparent and thus accessible? The archivist carries knowledge that will never make it into the database. On the one hand it’s tacit, on the other hand it has a clear relation to the process of archiving.

Plan rolls of Hans Hollein Archive at Az W depot, Möllersdorf, Halle 9 © Architekturzentrum Wien, Sammlung, Photo: Mara Trübenbach

During my time at the Az W, one of the things I had to do was to unpack old plans by Austrian architect Hans Hollein and inventory them. After a few plans, I got a sense for the style of the drawings and the methods used. I also sorted the paper by either size or property so that I could more easily put the plans back in the right box. Not only is this process functional, but to some extent I tapped back into the architects’ embodiment. Investing in a detailed drawing or an elaborate collage gave insight into the amount of information the file contains. Much like the time invested in a digital file, it is difficult to comprehend until the viewer has never created, thus experienced, such a file him-/herself. He or she could only guess at it, but never feel it. There are equivalences in the digital and embodied blind spots to be uncovered. It is literally about flattening of the dimension and who’s eye is looking at the plans. The material aspect is much more democratic. One would need a certain level of training to be able to read the plans fluently. The weakness and strength are one and the same intersection.

Close up of plan rolls of Hans Hollein Archive at Az W depot, Möllersdorf, Halle 9 © Architekturzentrum Wien, Sammlung, Photo: Mara Trübenbach

Unlike the digital archive, the physical archive is not sorted by project, but by type of support (drawing, model, photograph, etc). Not only the different treatment of the physical material, but also my motion sequences depended on the type. I unrolled plans and some of them were very fragile, not in relation to the material chosen, but to the technique used to make the drawing or collage. This sensitivity immediately reveals a certain attachment to the material. The memories and labour that went into it became clear to me through this sensory experience of touch that I remember how carefully I carried finished drawings into my study for final reviews, or when we printed competition plans and packed them extremely carefully into a box that would carry our vision to the committee. Since those memories had resurfaced, I also had a much easier time remembering where the archival material was kept and what it contained. According to Ahmed, “emotions are not “in” either the individual or the social, but produce the very surfaces and boundaries”.[1] The focus is on how emotions can be generated with and through art and architecture. I wonder if someone else who never had the experience of practicing architecture would feel the same way. In any case, the material helps build a relationship. These sense memories are also connected to the material properties. As I unrolled, flipped through, and rolled up the plans, I found that my attention was much more focused on the drawing when one of the papers stood out. This made me aware of noticing the material but not the drawing itself at first glance, which seems contradictory.

How could such emotions and memories in the archive be captured? And how can they be revealed when a scholar is researching a particular case? How can we remember and trigger emotions visually if we can’t touch them? These are questions that I take away from the archival secondment to address in my dissertation, which argues that material helps to literally bring emotions to the surface of the human body, which could provide new insights into the way we think surfaces and thus archives in the past, present, and future.

[1] Ahmed, Sara. 2014. “Introduction: Feel Your Way.” In The Cultural Politics of Emotion: Second Edition, 1–20. Edinburgh University Press.

(Un)packing drawings and plans of Austrian architect Hans Hollein at Az W depot, Möllersdorf, Halle 9 © Architekturzentrum Wien, Sammlung, Photo: Mara Trübenbach